Connecticut is the fifth most forested state. Our urban areas have the highest forest cover (67%) in the nation. Working on parallel tracks, members of the State Vegetation Management Task Force, led by Tom Degnan and Jeff Ward from the CT Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES), and faculty at the University of Connecticut, led by Tom Worthley and John Volin, have developed similar strategies to manage trees along the approximately 7,600 miles of roads that cross forested landscapes, in the traditional, rural sense.

At the suggestion of CT-DEEP, Division of Forestry, a collaborative team of scientists, along with DEEP, utilities, and private foresters, assembled to tackle the challenge of maintaining the aesthetic appeal of forested Connecticut byways while reducing the potential of tree-caused damage to the utility infrastructure (figure 1) during severe storms.

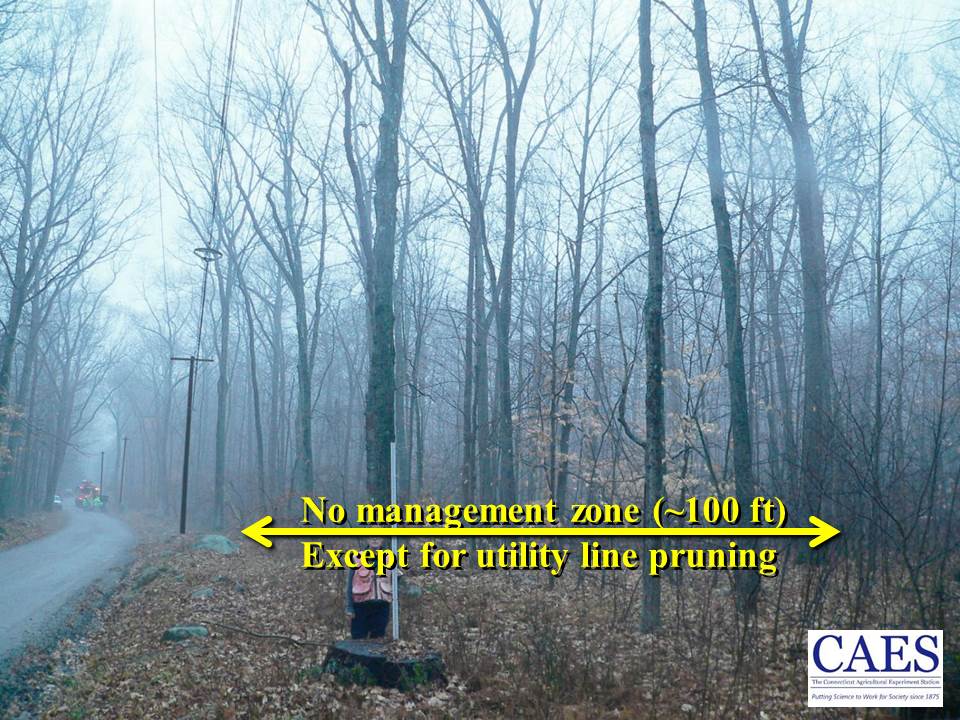

The “Stormwise” roadside forest management demonstration area along Gadpouch Road (figure 2) in Meshomasic State Forest supplies power for most of Colchester and sections of East Hampton and Hebron. Staff from CAES and UConn mapped and measured all trees (figure 3) in a strip approximately 130ft x 1300 ft. Along with standard forestry measurements like species, diameter and height, we measured factors like lean, crown asymmetry, internal decay, and dieback that increase the risk that a tree, or one of its branches, would fall onto the utility lines.

The Gadpouch Road site was the first of eight locations around the state, one in each county, that are being established as part of the “Stormwise” research initiative sponsored by the USDA Forest Service and supported by the electric utilities. The goal of the vegetation management component of the Stormwise project is to foster healthy, storm-resistant roadside forests by developing practical, cost-effective methods that meld arboricultural (individual tree care) and silviculture (forest management) practices.

"The goal of the vegetation management component is to foster healthy, storm-resistant roadside forests by developing practical, cost-effective methods that meld individual tree care and forest management practices."

After the trees had been measured, CL&P and DEEP foresters identified trees that were leaning towards the wires or that had severe defects increasing their risk of failing during severe weather. Because loggers will not cut trees that would fall on wires, the risk trees were removed by CL&P contractors and the logs taken to the DEEP depot to be made into lumber for use on state property - including new picnic tables. The remaining trees marked for removal were cut as part of a chainsaw safety class or sold to local firewood buyers. Small-scale harvesting methods coupled with value-added operations are being tested at another UConn Forest site and at Nathan Hale Forest.

Right tree, right place

What might be considered desirable roadside forest conditions? Imagine the immediate roadside forest edge being comprised of trees and shrubs that typically are short; dogwoods, ironwoods, shadbush and viburnums are some examples. Set back a bit from the utility lines would be widely spaced maples, beech, and oaks interspersed with shrubs, wildflowers, and ferns.

Widely spaced trees, such as those in open fields, develop crowns that are wide rather than tall, have stout stems and branches, and develop well‐anchored, widespread root systems. All of the characteristics of open‐grown trees make them more resistant to wind damage, especially to becoming wind thrown. These trees would still provide important aesthetic, hydrologic, and habitat benefits while remaining wind-firm and low-risk to power and road infrastructure.“The right tree in the right place” and the novel approach of establishing shorter trees with wide-spreading crowns, rather than tall, crowded, narrow-crowned trees, are two key suggestions that could improve roadside forest storm resilience.